Medieval India: Tripartite

Many dynasties emerged during 7th century.

By the 7th century there were big landlords or warrior chiefs in different regions of the subcontinent.

Existing kings often acknowledged them as their subordinates or samantas. As these samantas gained power and wealth, they declared themselves to be maha-samanta, maha- mandaleshvara (the great lord of a “circle” or region) and so on.

Sometimes they asserted their independence from their overlords.

Rashtrakutas in the Deccan is one such instance. Initially they were subordinate to the Chalukyas of Karnataka. In the mid-eighth century, Dantidurga, a Rashtrakuta chief, overthrew his Chalukya overlord.

In each states, resources were obtained from the producers, that is, peasants, cattle-keepers, artisans, who were often persuaded or compelled to surrender part of what they produced.

Prashastis contain details that may not be literally true. But they tell us how rulers wanted to depict themselves – as valiant, victorious warriors, for example.

However author named Kalhana composed Sanskrit poems in 12th century and he was critical about the rulers and their policies.

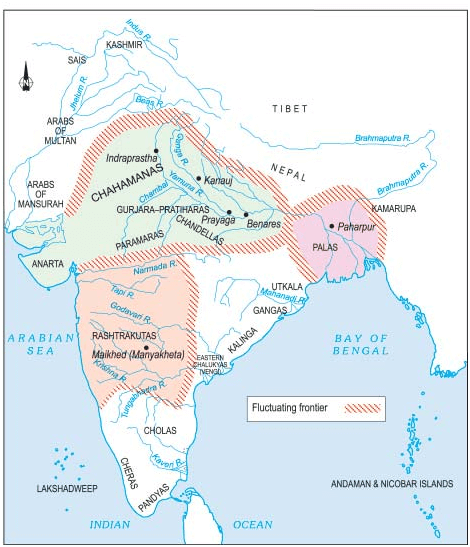

Kanauj in the Ganga valley was a prized area. For centuries, rulers belonging to the Gurjara-Pratihara, Rashtrakuta and Pala dynasties fought for control over Kanauj. Historians often describe it as the “tripartite struggle”.

Rulers also tried to demonstrate their power and resources by building large temples.

Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni, Afghanistan [ruled 997-1030] and extended control over Central Asia, Iran and north-west parts of subcontinent used to attack these temples including Somnath of Gujarat.

Al-Biruni, Gazni’s trusted scholar was made to write about to subcontinent he conquered. This arabic wrok Kitanb-al-Hind sought help from Sankrit scholars too.

Chauhans /Chahamanas, who ruled over the region around Delhi and Ajmer.

They attempted to expand their control to the west and the east, where they were opposed by the Chalukyas of Gujarat and the Gahadavalas of western Uttar Pradesh.

The best-known Chahamana ruler was Prithviraja III (1168-1192), who defeated an Afghan ruler named Sultan Muhammad Ghori in 1191, but lost to him the very next year, in 1192.

THE CHOLAS

Vijayalaya, who belonged to the ancient chiefly family of the Cholas from Uraiyur, captured the delta from the Muttaraiyar in the middle of the ninth century. He built the town of Thanjavur and a temple for goddess Nishumbhasudini there.

The successors of Vijayalaya conquered neighbouring regions and the kingdom grew.

Rajaraja I, considered the most powerful Chola ruler, became king in AD 985 and expanded the control.

Rajaraja’s son Rajendra I continued his policies and even raided the Ganga valley, Sri Lanka and countries of Southeast Asia, developing a navy for these expeditions.

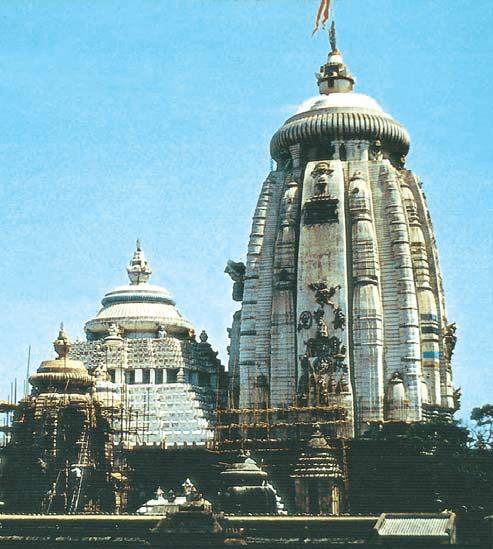

The big temples of Thanjavur and Gangaikonda- cholapuram, built by Rajaraja and Rajendra.

Chola temples often became the nuclei of settlements which grew around them. And these temples were not only places of worship; they were the hub of economic, social and cultural life as well.

Many of the achievements of the Cholas were made possible through new developments in agriculture.

Settlements of peasants, known as ur, became prosperous with the spread of irrigation agriculture. Groups of such villages formed larger units called nadu.

The village council and the nadu had several administrative functions including dispensing justice and collecting taxes.

Rich peasants of the Vellala caste exercised considerable control over the affairs of the nadu under the supervision of the central Chola govt.

Delhi as the center of attraction

When did Delhi became strategically important as center of political importance? Who were the major rules of Delhi during medieval period? Hopefully you will get answers to these questions in this post.

- Delhi became an important city only in the 12th century.

- Delhi first became the capital of a kingdom under the Tomara Rajputs, who were defeated in the middle of the twelfth century by the Chauhans .

Rajput Dynasty

- Tomaras [early twelfth century – 1165]

- Ananga Pala [1130 -1145]

- Chauhans [1165 -1192]

- Prithviraj Chauhan [1175 -1192]

Delhi Sultans

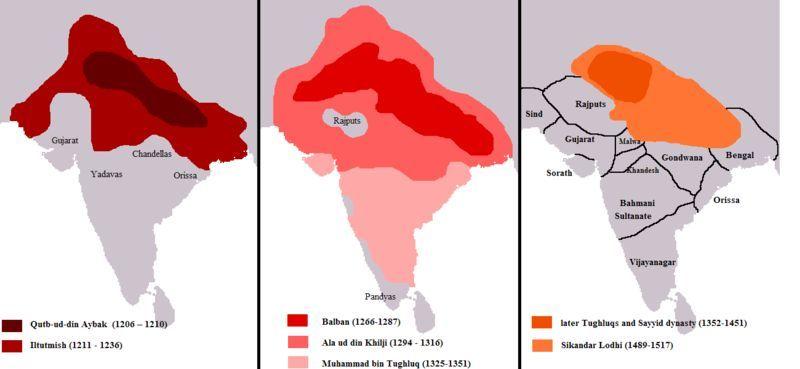

- By the 13th century Sultanates transformed Delhi into a capital that controlled vast areas of the subcontinent .

- “Histories”, tarikh (singular) / tawarikh (plural), written in Persian, the language of administration under the Delhi Sultans by learned men: secretaries, administrators, poets and courtiers who lived in cities (mainly Delhi) and hardly ever in villages.

- Objectives of these writings : (a) They often wrote their histories for Sultans in the hope of rich rewards (b) they advised rulers on the need to preserve an “ideal” social order based on birthright and gender distinctions (c) their ideas were not shared by everybody.

- In 1236 Sultan Iltutmish’s daughter, Raziyya, became Sultan. Nobles were not happy at her attempts to rule independently. She was removed from the throne in 1240.

Early Turkish [1206-1290]

- Qutbuddin Aybak [1206 -1210]

- Shamsuddin Iltutmish [1210 -1236]

- Raziyya [1236 -1240]

- Ghiyasuddin Balban [1266 -1287]

The expansion of the Delhi Sultanate

- In the early 13th century the control of the Delhi Sultans rarely went beyond heavily fortified towns occupied by garrisons.

- The Sultans seldom controlled the hinterland, the lands adjacent to a city or port that supply it with goods and services, of the cities and were therefore dependent upon trade, tribute or plunder for supplies.

- Controlling garrison towns in distant Bengal and Sind from Delhi was extremely difficult.

- The state was also challenged by Mongol invasions from Afghanistan and by governors who rebelled.

- The expansion occurred during the reigns of Ghiyasuddin Balban, Alauddin Khalji and Muhammad Tughluq.

Khalji Dynasty [1290 – 1320]

- Jalaluddin Khalji [1290 – 1296]

- Alauddin Khalji [1296 -1316]

Tughluq Dynasty [1320 – 1414]

- Ghiyasuddin Tughluq [1320-1324]

- Muhammad Tughluq [1324 -1351]

- Firuz Shah Tughluq [1351 -1388]

- So, what the first thing Sultans did were consolidating these hinterlands of the garrison towns. During these campaigns forests were cleared in the Ganga-Yamuna doab and hunter- gatherers and pastoralists expelled from their habitat.

- These lands were given to peasants and agriculture was encouraged. New fortresses and towns were established to protect trade routes and to promote regional trade.

- Secondly , expansion occurred along the “external frontier” of the Sultanate. Military expeditions into southern India started during the reign of Alauddin Khalji and culminated with Muhammad Tughluq.

Administration & Consolidation

- Rather than appointing aristocrats as governors, the early Delhi Sultans, especially Iltutmish, favoured their special slaves purchased for military service, called bandagan .

- The Khaljis and Tughluqs continued to use bandagan and also raised people of humble birth, who were often their clients, to high political positions.

- Slaves and clients were loyal to their masters and patrons, but not to their heirs.

- Authors of Persian tawarikhcriticised the Delhi Sultans for appointing the “low and base-born” to high offices.

- Military commanders were appointed as governors of territories . This land is called iqta and their holder called iqtadar or muqti . The duty of muqti was to lead military campaigns and maintain law and order in their iqtas.

- But still large parts of the subcontinent remained outside the control of the Delhi Sultans.

- The Mongols under Genghis Khan invaded Transoxiana in north-east Iran in 1219 and the Delhi Sultanate during the reign of Alauddin Khalji and Muhammad Tughluq .

A.Khalji’s defensive policy against Genghis

- As a defensive measure, Alauddin Khalji raised a large standing army.

- Constructed a new garrison town named Siri for his soldiers.

- In order to feed soldiers, produce collected as tax from lands was done and paddy has got fixed tax as 50% of the yield.

- Alauddin chose to pay his soldiers salaries in cash rather than iqtas. He made sure merchants sell supplies to these soldiers according to prescribed prices .

- So here A.Khalji’s administrative measure were highly praised due to effective intervention in markets to have prices unders control .

- He successfully withstood the threat of Mongol invasions .

M.Tughluq offensive policy against Genghis

- The Mongol army was defeated earlier. M.Tughluq still raised a large standing army.

- Rather than constructing a new garrison town he emptied the residents of a Delhi city named Delhi-i Kuhna and the soldiers garrisoned there.

- Produce from the same area was collected as tax and additional taxes to feed the large army. This coincided with famine in the area. .

- Muhammad Tughluq also paid his soldiers cash salaries. But instead of controlling prices, he used a “token” currency. This cheap currency could be counterfeited easily because it was made of “bronze”.

- His campaign into Kashmir was a disaster. He then gave up his plans to invade Transoxiana and disbanded his large army .

- His administrative measures created complications. The shifting of people to Daulatabad was resented. The raising of taxes and famine in the Ganga-Yamuna belt led to widespread rebellion. And finally, the “token” currency had to be recalled.

15th & 16th Century Sultanates: Sayyid, Lodi and Suri

Sayyid Dynasty [1414 – 1451]

- Khizr Khan 1414 -1421

Lodi Dynasty [1451 – 1526]

- Bahlul Lodi 1451 -1489

Suri Dynasty [1540-1555]

- Sher Shah Suri [1540-1545] captured Delhi.

- For the first time during the Islamic conquest the relationship between the people and the ruler was systematized, with little oppression or corruption.

- He challenged and defeated the Mughal emperor Humayun (1539 : Battle of Chausa, 1540 : Battle of Kannauj)

- Sher Shah introduced an administration that borrowed elements from Alauddin Khalji and made them more efficient.

- Sher Shah’s administration became the model followed by the great emperor Akbar (1556-1605) when he consolidated the Mughal Empire.

- His tomb is at Sasaram [Bihar

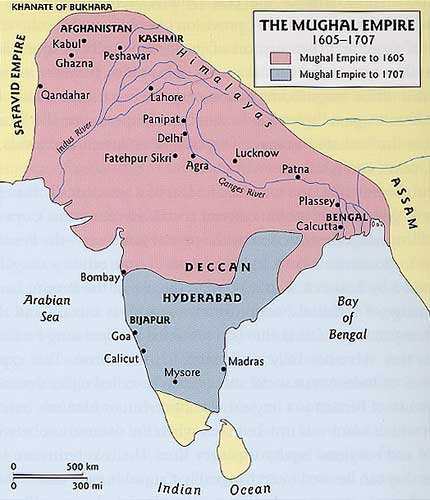

The Mughal Dynasty

- From the latter half of the 16th century, they expanded their kingdom from Agra and Delhi until in the 17th century they controlled nearly all of the subcontinent.

- They imposed structures of administration and ideas of governance that outlasted their rule, leaving a political legacy that succeeding rulers of the subcontinent could not ignore.

Babur – The Founder of Mughal Empire

- The first Mughal emperor (1526- 1530)

- Political situation in north-west India was suitable for Babur to enter India .

- Sikhandar Lodi died in 1517 and Ibrahim Lodi succeded him. I. Lodhi tried to create a strong centralised empire which alarmed Afghan chiefs as well as Rajaputs.

- So in 1526 he defeated the Sultan of Delhi, Ibrahim Lodi and his Afghan supporters, at (First) Panipat (War) and captured Delhi and Agra.

- The establishment of an empire in the Indo-Gangetic valley by Babur was a threat to Rana Sanga.

- So in 1527 – defeated Rana Sanga, Rajput rulers and allies at Khanwa [a place west of Agra].

- Babur’s advent was significant :

- Kabul and Qandhar became an integral part of an empire comprising North India . Since these areas had always acted as a staging place for an invasion of India and provide security from external invasions

- These two areas mentioned above helped to strengthen India’s foreign trade with China and Mediterranean seaports .

- His war tactics were very expensive since he used heavy artillery which ended the era of small kingdoms because these smaller ones cant afford it .

- He introduced a concept of the state which has to be based on strength and prestige of Crown instead of religious interference. This provided a precedent and direction to his successors .

Humayun [1530-1540, 1555-1556]

- Humayun divided his inheritance according to the will of his father. His brothers were each given a province.

- Sher Khan defeated Humayun which made him forced to flee to Iran.

- In Iran, Humayun received help from the Safavid Shah. He recaptured Delhi in 1555 but died in an accident the following year.

Akbar [1556-1605] – The Most Popular Ruler among the Mughal Dynasty

His reign can be divided into three periods :

- 1556-1570 : Military campaigns were launched against the Suris and other Afghans, against the neighbouring kingdoms of Malwa and Gondwana, and to suppress the revolt of Mirza Hakim and the Uzbegs. In 1568 the Sisodiya capital of Chittor was seized and in 1569 Ranthambhor.

- 1570-1585 : military campaigns in Gujarat were followed by campaigns in the east in Bihar, Bengal and Orissa.

- 1585-1605 : expansion of Akbar’s empire. Qandahar was seized from the Safavids, Kashmir was annexed, as also Kabul . Campaigns in the Deccan started and Berar, Khandesh and parts of Ahmadnagar were annexed.

Jahangir [1605-1627]

- Military campaigns started by Akbar continued.

- The Sisodiya ruler of Mewar, Amar Singh, accepted Mughal service. Less successful campaigns against the Sikhs, the Ahoms and Ahmadnagar followed.

Shah Jahan [1627-1658]

- Mughal campaigns continued in the Deccan under Shah Jahan.

- The Afghan noble Khan Jahan Lodi rebelled and was defeated.

- In the north-west, the campaign to seize Balkh from the Uzbegs was unsuccessful and Qandahar was lost to the Safavids.

- Shah Jahan was imprisoned by his son Aurangazeb for the rest of his life in Agra.

Aurangzeb [1658-1707]

- In the north-east, the Ahoms [a kingdom in Assam near Brahmaputra valley] were defeated in 1663, but they rebelled again in the 1680s. Because Ahoms successfully resisted Mughal expansion for a long time and they dont want to give up their sovereignty which they were enjoying for 600 years .

- Campaigns in the north-west against the Yusufzai and the Sikhs were temporarily successful.

- Mughal intervention in the succession and internal politics of the Rathor Rajputs of Marwar led to their rebellion.

- Campaigns against the Maratha chieftain Shivaji were initially successful. However, escaped from Aurangzeb’s prison Shivaji declared himself an independent king and resumed his campaigns against the Mughals.

- Prince Akbar[II] rebelled against Aurangzeb and received support from the Marathas and Deccan Sultanate.

- After Akbar’s rebellion, Aurangzeb sent armies against the Deccan Sultanates. Bijapur[Karnataka] was annexed in 1685 and Golcunda [Telangana] in 1687.

- From 1698 Aurangzeb personally managed campaigns in the Deccan against the Marathas who started guerrilla warfare.

- Aurangzeb also had to face the rebellion in north India of the Sikhs, Jats and Satnamis . The Satnamis were a sect of Hinduism and they were resented against Aurangzeb’s strict Islamic policies – which included reviving the hated Islamic Jiziya tax (poll tax on non-Muslim subjects), banning music and art, and destroying Hindu temples .

Mughal relations with other rulers

- The Mughal rulers campaigned constantly against rulers who refused to accept their authority.

- However, as the Mughals became powerful many other rulers also joined them voluntarily. eg : Rajaputs.

- The careful balance between defeating but not humiliating their opponents [but not with Shivaji by Aurangzeb] enabled the Mughals to extend their influence over many kings and chieftains.

Mansabdars and Jagirdars

- As the empire expanded to encompass different regions the Mughals recruited diverse bodies of people like Iranians, Indian Muslims, Afghans, Rajputs, Marathas and other groups.

- Those who joined Mughal service were enrolled as mansabdars – an individual who holds a mansab, meaning a position or rank.

- It was a grading system used by the Mughals to fix rank, salary and military responsibilities.

- The mansabdar’s military responsibilities required him to maintain a specified number of sawar or cavalrymen.

- Mansabdars received their salaries as revenue assignments – jagirs which were somewhat like iqtas. But unlike muqtis, mansabdars dint administer jagirs, instead only had rights to collect the revenue that too by their servants while manasbdars themselves served in some other part of the country.

- In Akbar’s reign, these jagirs were carefully assessed so that their revenues were roughly equal to the salary of the mansadar.

- But by Auragzeb’s reign, there was a huge increase in the number of mansabdars which meant a long wait before they received a jagir.

- So the shortage of jagirdars was witnessed and whoever got jagirs they extracted more revenue than allowed .

- Aurangzeb couldn’t control this development and the peasantry therefore suffered tremendously.

Zabt and Zamindars

- To sustain Mughul administration , rulers relied on extracting taxes from rural produce[peasantry].

- Mughal used one term – zamindars – to describe all intermediaries, whether they were local headmen of villages or powerful chieftains who collect these taxes for rulers.

- Careful survey was done to evaluate crop yields .

- On the basis of this data , the tax was fixed.

- Each province was divided into revenue circles with its own schedule of revenue rates for individual crops. This revenue system was known as zabt.

- However, rebellious zamidars were present . They challenged the stability of the Mughal Empire from the end of the 17th century through peasant revolt.

Akbar Nama & Ain-i Akbari

- Abul Fazl wrote a three volume history of Akbar’s reign titled, Akbar Nama .

- The first volume dealt with Akbar’s ancestors .

- The second recorded the events of Akbar’s reign.

- The third is the Ain-i Akbari. It deals with Akbar’s administration, household, army, the revenues and geography of his empire. It provides rich details about the traditions and culture of the people living in India. It also got statistical details about crops, yields, prices, wages and revenues.

Akbar’s policies

- The empire was divided into provinces called subas, governed by a subadar who carried out both political and military functions.

- Subadar was supported by other officers such as the military paymaster (bakhshi), the minister in charge of religious and charitable patronage (sadr), military commanders (faujdars) and the town police commander (kotwal).

- Each province had a financial officer or diwan.

- Akbar’s nobles commanded large armies and had access to large amounts of revenue.

- Akbar’s discussions on religion with the ulama, Brahmanas, Jesuit priests who were Roman Catholics, and Zoroastrians took place in the ibadat khana.

- He realised that religious scholars who emphasised ritual and dogma were often bigots. Their teachings created divisions and disharmony amongst his subjects. This eventually led Akbar to the idea of sulh-i kul or “universal peace”.

- Abul Fazl helped Akbar in framing a vision of governance around this idea of sulh-i kul.

- This principle of governance was followed by Jahangir and Shah Jahan as well.

17th century and after

- Despite economical and commercial prosperity inequalities were a glaring fact. Poverty existed side by side with the greatest opulence.

- At the time of Shahjahan’s reign, highest ranking mansabdars were nominal and they are the ones who receive maximum salaries than others .

- The scale of revenue collection[tax] left very little for investment [in tools and supplies] in the hands of the primary producers – the peasant and the artisan.

- As the authority of the Mughal emperor slowly declined, his servants emerged as powerful centres of power in the regions. They constituted new dynasties and held command of provinces like Hyderabad and Awadh but still were loyal to Mughals.

- By the 18th century, the provinces of the empire had consolidated their independent political identities.

Rulers and Buildings – Medieval India

- Between the 8th and the 18th centuries kings and their officers built two kinds of structures: First were forts, palaces and tombs. Second were structures meant for public activity including temples, mosques, tanks, wells, bazaars.

- By making structures for subjects’ use and comfort, rulers hoped to win their praise.

- Construction activity was also carried out by others, including merchants. However, domestic architecture – large mansions (havelis) of merchants – has survived only from the eighteenth century.

Engineering Skills and Construction

- Monuments provide an insight into the technologie used for construction.

- Between the 7th and 10th centuries architects started adding more rooms, doors and windows to buildings using “trabeate” or “corbelled” design.

- Corbelled: roofs, doors and windows were made by placing a horizontal beam across two vertical columns.

From the 12th century onwards certain changes were visible .

- Arcuate“ type design started to appear. Here the weight of the superstructure above doors and windows was carried by the arches . The “keystone” at the centre of the arch transferred the weight of the superstructure to the base of the arch.

- Limestone cement was increasingly used in construction. This was very high quality cement .

Building Temples, Tanks and Mosques

- Hindu rulers took gods’ name. Eg: Rajarajeshvara temple was built by King Rajarajadeva for the worship of his god, Rajarajeshvaram.

- Muslim Sultans and Padshahs did not claim to be incarnations of god but Persian court chronicles

described the Sultan as the “Shadow of God”. - Water availability: Sultan Iltutmish [13th century] won respect for constructing a large reservoir just outside Dehli-i kuhna. It was called the hauz-i Sultani or the “King’s Reservoir”.

Religious construction: Why were temples constructed and destructed?

- As each new dynasty came to power, kings/emperors wanted to emphasise their moral right to be rulers.

- So constructing places of worship provided rulers with the chance to proclaim their close relationship with God, especially important in an age of rapid political change.

- Because kings built temples to demonstrate their devotion to God and their power and wealth, it is not surprising that when they attacked one another’s kingdoms, they often targeted these buildings. (Eg: Pandyan king Shrimara Shrivallabha, Chola king Rajendra I, Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni etc.)

Gardens, Tombs and Forts

- Under the Mughals, architecture became more complex.

- During Babur reign formal gardens, placed within rectangular walled enclosures and divided into four quarters by artificial channels. These gardens were known as chahar bagh, four gardens.

- The central towering dome and the tall gateway (pishtaq) became important aspects of Mughal architecture, first visible in Humayun’s tomb.

- Associated with the chahar bagh there was tradition known as “eight paradises” or hasht bihisht – a central hall surrounded by eight rooms.

- During Shah Jahan’s reign that the different elements of Mughal architecture were fused together in a harmonious synthesis. The ceremonial halls of public and private audience (diwan-i khas or am) were carefully planned. These courts were also described as chihil sutun or forty-pillared halls, placed within a large courtyard.

- Shah Jahan’s audience halls were specially constructed to resemble a mosque. The pedestal on which his throne was placed was frequently described as the qibla, the direction faced by Muslims at prayer.

- The connection between royal justice and the imperial court was emphasised by Shah Jahan in his newly constructed court in the Red Fort at Delhi.

- Court in Redfort by Shahjahan got a series of pietra dura [a Roman Art by inlaying of pieces of coloured stones resulting into some images] inlays that depicted the legendary Greek god Orpheus playing the lute[a string instrument]

- The construction of Shah Jahan’s audience hall aimed to communicate that the king’s justice would treat the high and the low as equals where all could live together in harmony.

- Shah Jahan adapted the river-front garden [a variation of chahar bagh] in the layout of the Taj Mahal.

- Only specially favoured nobles were given access to the river. All others had to construct their homes in the city away from the River Yamuna.

Region and Empire

- There was also a considerable sharing of ideas across regions: the traditions of one region were adopted by another. In Vijayanagara, for example, the elephant stables of the rulers were strongly influenced by the style of architecture found in the adjoining Sultanates of Bijapur and Golcunda.

- In Vrindavan, near Mathura, temples were constructed in architectural styles that were very

similar to the Mughal palaces in Fatehpur Sikri. - Mughal rulers were particularly skilled in adapting regional architectural styles in the construction of their own buildings

Towns of Medieval India

There were administrative centres, temple towns, as well as centres of commercial activities and craft production during medieval periods.

Administrative Centres and Towns

- The best example is Thanjavur.

- During the reign of Chola Dynasty (King Rajaraja Chola), its capital was Thanjavur.

- Architect Kunjaramallan Rajaraja Perunthachchan built Rajarajeshwara Temple.

- Besides the temple, there were palaces with mandapas or pavilions. where kings hold court here and issue order to subordinates.

- The Saliya weavers of Thanjavur and the nearby town of Uraiyur were busy producing cloth for flags to be used in the temple festival, fine cottons for the king and nobility and coarse cotton for the masses.

- Some distance away at Svamimalai, the sthapatis or sculptors were making exquisite bronze idols and tall, ornamental bell metal lamps.

Temple Towns and Pilgrimage Centres

- Thanjavur is also an example of a temple town. Temple towns represent a very important pattern of urbanisation, the process by which cities develop.

- Towns emerged around temples such as those of Bhillasvamin (Bhilsa or Vidisha in Madhya Pradesh), and Somnath in Gujarat. Other important temple towns included Kanchipuram and Madurai in Tamil Nadu, and Tirupati in Andhra Pradesh.

- Pilgrimage centres also slowly developed into townships. Vrindavan (Uttar Pradesh) and Tiruvannamalai (Tamil Nadu) are examples of two such towns.

Small towns

- From the 8th century onwards the subcontinent was dotted with several small towns. These probably emerged from large villages. They usually had a mandapika (or mandi of later times) to which nearby villagers brought their produce to sell. They also had market streets called hatta (haat of later times) lined with shops.

- Usually a samanta or, in later times, a zamindar built a fortified palace in or near these towns. They levied taxes on traders, artisans and articles of trade and sometimes “donated” the “right” to collect these taxes to local temples .

Traders

- There were many kind of traders including Banjaras. (2016 Prelims Question)

- Since traders had to pass through many kingdoms and forests, they usually travelled in caravans and formed guilds[associations for certain tasks]to protect their interests. Manigramam and Nanadesi were two such guilds.These guilds traded extensively both within the peninsula and with Southeast Asia and China.

- The towns on the west coast were home to Arab, Persian, Chinese, Jewish and Syrian Christian traders.

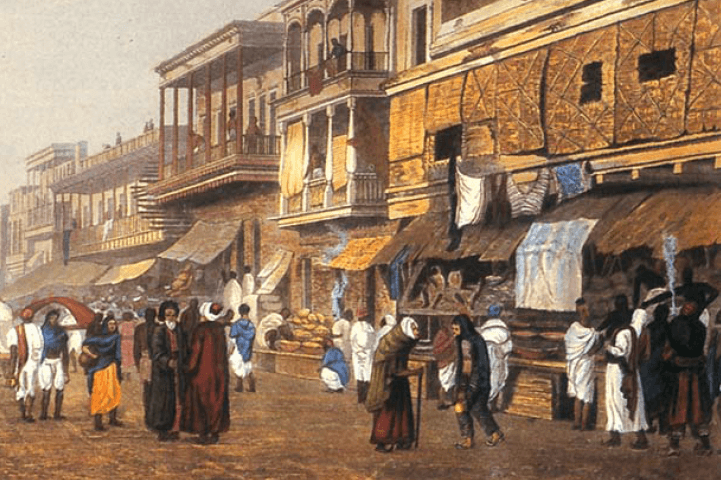

- At the same time Kabul [Afghanistan]became politically and commercially important from the 16th century onwards. Trade in horses was primarily carried here. Slaves were also brought here for sale.

Craftpersons

- The craftspersons of Bidar were so famed for their inlay work in copper and silver that it came to

be called Bidri. - The Panchalas or Vishwakarma community, consisting of goldsmiths, bronzesmiths, blacksmiths, masons and carpenters, were essential to the building of temples.

- They also played an important role in the construction of palaces, big buildings, tanks and reservoirs.

- Similarly, weavers such as the Saliyar or Kaikkolars emerged as prosperous communities, making donations to temples.

- Some aspects of cloth making like cotton cleaning, spinning and dyeing became specialised and independent crafts.

Major Towns: Surat, Hampi and Masulipattanam

Surat, Hampi and Masulipattanam were the major towns in India during the medieval period.

Hampi

- Located in the Krishna-Tungabhadra basin.

- It was the nucleus of the Vijayanagara Empire (1336).

- No mortar or cementing agent was used in the construction of fortified walls and the technique followed was to wedge them together by interlocking.

- It got splendid arches, domes and pillared halls with niches for holding sculptures.

- During 15th – 16th centuries, Hampi bustled with commercial and cultural activities. Moors (a name used collectively for Muslim merchants), Chettis and agents of European traders such as the Portuguese, thronged the markets of Hampi.

- Temples were the hub of cultural activities and devadasis (temple dancers) performed before the deity, royalty and masses in the many-pillared halls in the Virupaksha (a form of Shiva) temple.

- Hampi fell into ruin following the defeat of Vijayanagara in 1565 by the Deccani Sultans – the rulers of Golconda, Bijapur, Ahmadnagar, Berar and Bidar.

Surat

- It was an emporium of western trade during the Mughal period along with Cambay (present Khambat).

- Surat was the gateway for trade with West Asia via the Gulf of Ormuz. Surat has also been called the gate to Mecca because many pilgrim ships set sail from here.

- In the 17th century the Portuguese, Dutch and English had their factories and warehouses at Surat.

- The textiles of Surat were famous for their gold lace borders (zari) and had a market in West Asia, Africa and Europe.

- Decline factors: the loss of markets and productivity, control of the sea routes by the Portuguese, competition from Bombay where the English East India Company shifted its headquarters in 1668.

Masulipatnam

- Lay on the delta of the Krishna river.

- Both the Dutch and English East India Companies attempted to control Masulipatnam.

- The fort at Masulipatnam was built by the Dutch.

- The Qutb Shahi rulers of Golconda imposed royal monopolies on the sale of textiles, spices and other items to prevent the trade passing completely into the hands of the various East India Companies.

- In 1686-1687 Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb annexed Golconda.

- So European Companies took alternatives to Bombay, Calcutta and Madras which lost Masulipatanam’s glory.

Different kinds of societies: Those who followed rules of varna and those who didn’t

We have already seen that there were administrative centers, temple towns, as well as centers of commercial activities and craft production during medieval periods. But different kinds of societies evolved differently social change was not the same everywhere.

In many parts of the subcontinent, the society was already divided according to the rules of varna. These rules, as prescribed by the Brahmanas, were accepted by the rulers of large kingdoms. Under the Delhi Sultans and the Mughals, the hierarchy between social classes grew further.

However, there were other societies as well. Many societies in the subcontinent did not follow the social rules and rituals prescribed by the Brahmanas. Nor were they divided into numerous unequal classes. Such societies are often called tribes.

Beyond Big Cities: Tribal Societies

- Some powerful tribes controlled large territories. In Punjab, the Khokhar tribe was very influential during the 13th and 14th centuries.

- Kamal Khan Gakkhar, of Gakkhar tribe, was a noble (mansabdar) by Emperor Akbar.

- In Multan and Sind, the Langahs and Arghuns dominated extensive regions before they were subdued by the Mughals.

- In the western Himalaya lived the shepherd tribe of Gaddis.

- The distant north-eastern part of the subcontinent too was entirely dominated by tribes – the Nagas, Ahoms etc.

- In many areas of present-day Bihar and Jharkhand, Chero, chiefdoms had emerged by the 12th century. Raja Man Singh, Akbar’s general, attacked and defeated them in 1591.

- The Maharashtra highlands and Karnataka were home to Kolis[also in Gujarat], Berads etc.

- South got Koragas, Vetars, Maravars etc.

- Bhils spread across western and central India. By the late 16th century, many of them had become settled agriculturists and some even zamindars.

- The Gonds were found in great numbers across the present-day states of Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh.

Gond Tribe

- They lived in a vast forested region called Gondwana.

- They practiced shifting cultivation.

- The Akbar Nama, a history of Akbar’s reign, mentions the Gond kingdom of Garha Katanga that had 70,000 villages.

- The administrative system of these kingdoms was becoming centralized.

- The emergence of large states changed the nature of Gond society.

- Certain Gond chiefs now wished to be recognized as Rajputs.

Ahom Tribe

- They migrated to the Brahmaputra valley from present-day Myanmar in the 13th century.

- They created a new state by suppressing the older political system of the bhuiyans (landlords).

- During the 16th century, they annexed the kingdoms of the Chhutiyas (1523) and of Koch-Hajo (1581) and subjugated many other tribes.

- They know to use firearms as early as the 1530s.

- In 1662, the Mughals under Mir Jumla attacked the Ahom kingdom and defeated them.

- The Ahom state depended upon forced labour. Those forced to work for the state were called paiks.

- By the 17th century, the administration became quite centralized.

- In their worship concepts influence of Brahmanas increased by the 17th century.

- Literature and culture flourished in their time. Works known as buranjis, were written – first in the Ahom language and then in Assamese.

Trader Nomads: Banjaras

- The Banjaras were the most important trader-nomads. Their caravan was called tanda.

- Alauddin Khalji used the Banjaras to transport grain to the city markets.

- Emperor Jahangir wrote in his memoirs about Banjaras.

Brahminism vsBuddhism/Jainism vsDevotional Paths (Bhakitsm, Sufism, and Sikhism)

Brahminism based on caste-system was prominent during the Medieval period. But there was opposition to the same as well.

Many people were uneasy with such ideas and turned to the teachings of the Buddha or the Jainas according to which it was possible to overcome social differences and break the cycle of rebirth through

personal effort.

Others felt attracted to the idea of a Supreme God who could deliver humans from such bondage if approached with devotion (or bhakti). This idea, advocated in the Bhagavadgita, grew in popularity in the early centuries of the Common Era.

Intense devotion or love of God is the legacy of various kinds of bhakti and Sufi movements that have evolved since the eighth century. The idea of bhakti became so popular that even Buddhists and Jainas adopted these beliefs.

Bhakti cult

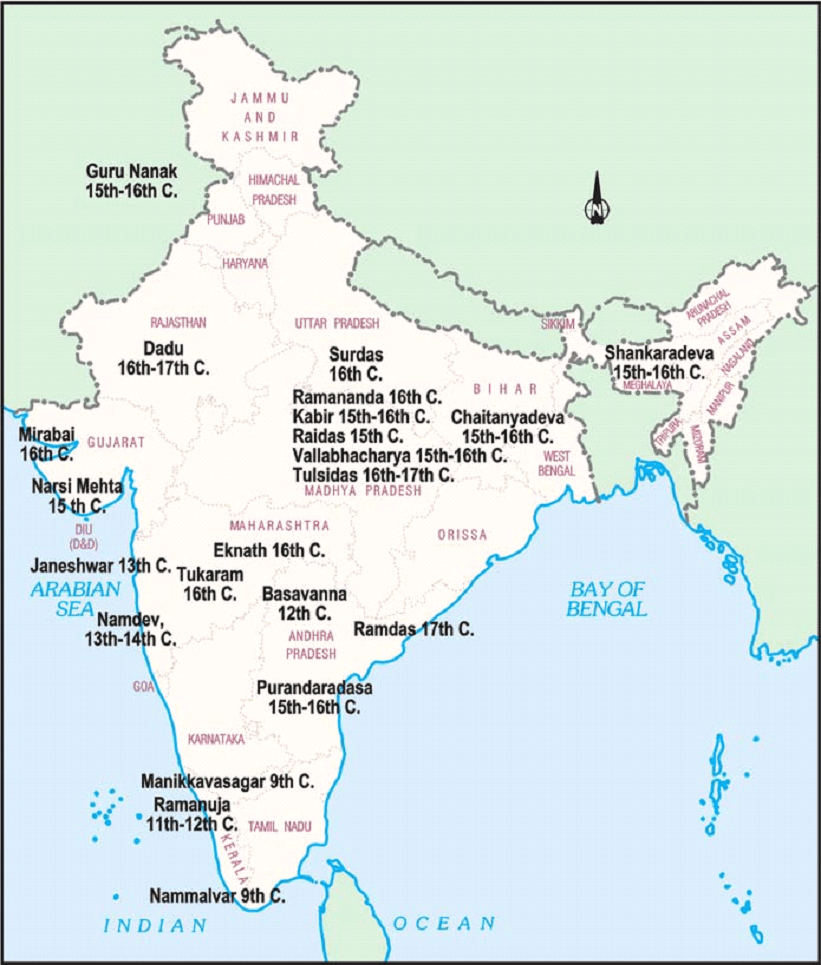

Bhakti was accepted as a means to attain moksha along with jnana and karma. The development of this cult took place in South India when the Nayanars and Alwars moved against the austerities propagated by the Buddhist and Jain schools and professed that ultimate devotion to god was the means to salvation.

People were no longer satisfied with a religion which emphasized only ceremonies. The cult is the combined result of the teachings of various saints, through the then times. Each of them had their own views, but the ultimate basis of the cult was a general awakening against useless religious practices and unnecessary strictness. The cult also emerged as a strong platform against casteism.

Some of the important leaders of the movement are:

- Namadeva and Ramananda (Maharashtra and Allahabad) – Both of them taught the concept of bhakti to all the four varnas and disregarded the ban on people of different castes cooking together and sharing meals.

- Sankara and Ramanuja – The propounders of Advaita (non-duality) and vishishta adwaitha (qualified non-duality) respectively. They believed god to be nirguna parabrahma and satguna parabrahma respectively.

- Vallabhacharya – propounder of shuddha adwaitha or pure non-duality.

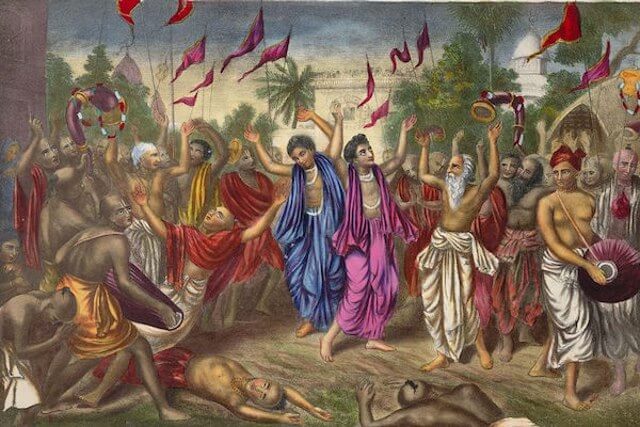

- Chaitanya (Bengal) – relied on the use of music, dance and bhajans to get in touch with God. ‘love’ was the watchword of the chaitanya cult.

- Kabir – was a disciple of Ramananda, and was raised by a Muslim weaver. He stood for doing away with all the unnecessary customs and rituals in both religions and bringing union between these religions.

- Guru Nanak.

- Nimbakacharya – founder of the Radha-Krishna cult. He expressed this relation to substantiate the importance of marriage. It was also used as an example of God’s love to the people.

Nayanars and Alvars

- In South India 7th to 9th centuries saw the emergence of new religious movements, led by the Nayanars (saints devoted to Shiva) and Alvars (saints devoted to Vishnu) who came from all castes including those considered “untouchable” like the Pulaiyar and the Panars.

- They were sharply critical of the Buddhists and Jainas.

- They drew upon the ideals of love and heroism as found in the Sangam literature (Tamil literature).

- Between 10th and 12th centuries the Chola and Pandya kings built elaborate temples around many of the shrines visited by the saint-poets, strengthening the links between the bhakti tradition and temple worship.

Philosophy and Bhakti

- Shankara, from Kerala in the 8th century, salvation .was an advocate of Advaita or the doctrine of the oneness of the individual soul and the Supreme God which is the Ultimate Reality.

- He taught that Brahman, the only or Ultimate Reality, was formless and without any attributes.

- He considered the world around us to be an illusion or maya, and preached renunciation of the world and adoption of the path of knowledge to understand the true nature of Brahman salvation.

- Ramanuja, from Tamil Nadu in the 11th century, propounded the doctrine of Vishishtadvaita or qualified oneness in that the soul, even when united with the Supreme God, remained distinct.

- Ramanuja’s doctrine inspired the new strand of bhakti which developed in north India subsequently.

Basavanna’s Virashaivism

- This movement began in Karnataka in the 12th century which argued for the equality of all human beings and against Brahmanical ideas about caste and the treatment of women.

- They were also against all forms of ritual and idol worship.

Saints of Maharashtra

- The most important among them were Janeshwar, Namdev, Eknath and Tukaram as well as women like Sakkubai and the family of Chokhamela, who belonged to the “untouchable” Mahar caste.

- This regional tradition of bhakti focused on the Vitthala (a form of Vishnu) temple in Pandharpur, as well as on the notion of a personal god residing in the hearts of all people.

- These saint-poets rejected all forms of ritualism, outward display of piety and social differences based on birth.

- It is regarded as a humanist idea, as they insisted that bhakti lay in sharing others’ pain.

Nathpanthis, Siddhas, and Yogis

- Criticised the ritual and other aspects of conventional religion and the social order, using simple, logical arguments.

- They advocated renunciation of the world.

- To them, the path to salvation lay in meditation on the formless Ultimate Reality and the realization of oneness with it.

- To achieve this they advocated intense training of the mind and body through practices like yogasanas, breathing exercises and meditation.

- These groups became particularly popular among “low” castes.

Saint Kabir

- Probably lived in the 15th-16th centuries.

- We get to know of his ideas from a vast collection of verses called sakhis and pads said to have been composed by him and sung by wandering bhajan singers.

- Some of these were later collected and preserved in the Guru Granth Sahib, Panch Vani, and Bijak.

- Kabir’s teachings were based on a complete, rejection of the major religious traditions and caste systems. He believed in a formless Supreme God and preached that the only path to salvation was through bhakti or devotion.

- The language of his poetry was simple which could even be understood by ordinary people.

- He sometimes used cryptic language, which was difficult to follow.

- He drew his followers from among both Hindus and Muslims.

Sufi Movement and Islam

The word Sufi means wool. The preachers from Arabia wore wool to protect themselves from dust winds. The Sufi movement is believed to have begun in Persian countries against the highly puritan Islamic culture.

Later, it spread into India and adopted various things like yogic postures, dance and music into it, and turned itself into a pantheistic movement. The Sufi orders were of two types – ba-shara and be-shara, where shara stood for the Islamic law. The former obeyed the laws while the latter was more liberal.

The saints organized themselves into twelve silsilas or orders. The important among them were the Chisti and Suhrawardi silsilas, both of which belonged to the ba-shara order.

The Chisti Silsila was begun by Khwaja Moinuddin Chisti who came to India around 1192. None of his records remain, and he is widely known through the writings of his disciples and followers. The most famous of the Chisti saints were Nizamuddin Auliya and Naziruddin chirag-i-Delhi. They mingled freely with people of low classes, even Hindus. The chistis didn’t want anything to do with the administration or money. They led simple austere lives.

This was just the opposite in the case of the suhrawardi saints who were rich, and often held positions in the government. Bahauddin Zachariah suhrawardi is a famous saint from this silsila.

There were two streams in general – wahdat-ul-wujud (doctrine of the unity of god) and wahdat-ul-shuhud (philosophy of apprenticism). The latter was found only in the nakshbandi silsila, which was a highly puritan Islamic silsila.

THINGS TO NOTE:

- Sufis were Muslim mystics and who composed poems.

- They adopted many ideas of each other[religions].

- They rejected outward religiosity and emphasized love and devotion to God and compassion towards all fellow human beings.

- Silsilas, a genealogy of Sufi teachers, each following a slightly different method (tariqa) of instruction and ritual practice.

- Islam propagated strict monotheism or submission to one God. Muslim scholars developed a holy law called Shariat.

- The Sufis often rejected the elaborate rituals and codes of behaviour demanded by Muslim religious scholars.

Baba Guru Nanak (1469-1539) and Sikhism

- Established a centre at Kartarpur named Dera Baba Nanak on the river Ravi.

- The sacred space thus created by Guru Nanak was known as dharmsal. It is now known as Gurdwar.

- Before his death Guru appointed Lehna also known as Guru Angadas his successor.

- Guru Angad compiled the compositions of Guru Nanak, to which he added his own in a new script known as Gurmukhi.

- The three successors of Guru Angad also wrote under the name of “Nanak” and all of their compositions were compiled by Guru Arjan [5th Guru who was executed by Jehangir]in 1604.

- The compilation was added with the writings of other figures like Shaikh Farid, Sant Kabir, Bhagat Namdev and Guru Tegh Bahadur.

- In 1706 this compilation was authenticated by Guru Gobind Singh. It is now known as Guru Granth Sahib.

- Due to Guru Nanak’s insistence that all the followers should adopt productive and useful occupations had received wider support during 16th century and followers increased, henceforth.

- By the beginning of the 17th century, the town of Ramdaspur (Amritsar) had developed around the central Gurdwara called Harmandar Sahib (Golden Temple). It was virtually self-governing and also referred as ‘a state within the state’ community. This fumed Mughal emperor Jahangir which led to the execution of Guru Arjan in 1606.

- The Sikh movement began to get politicized in the 17th century, a development which culminated in the institution of the Khalsa by Guru Gobind Singh in 1699 and this entity is called as Khalsa Panth.

- Guru Nanak’s idea of equality had social and political implications because his idea of liberation was not that of a state of inert bliss but rather the pursuit of active life with a strong sense of social commitment.

Summary

The coming of the Turks to the Indian sub-continent led to a revamp of culture, religion, architecture and almost all fields of life. This was due to the two strongly established religious views that confluence here. The strong Islamic views of the Turks combined with the established Hinduistic culture already prevalent in India. Both Sufism and Bhakti cult were out-of-the-box thoughts on religion. They were mainly against the common religious views, and most importantly, they both were strongly against the caste system.

Medieval India: Regional Cultures

The frontiers separating regions have evolved over time are still changing. What we understand as regional cultures today are often the product of complex processes of intermixing of local traditions with ideas from other parts of the subcontinent. In this post, let us quickly go through some of the regional cultures of India during the medieval period.

Kerala: The Cheras and Malayalam

- The Chera kingdom of Mahodayapuram was established in the 9th century in the south-western part of the peninsula, part of present-day Kerala.

- It is likely that Malayalam was spoken in this area.

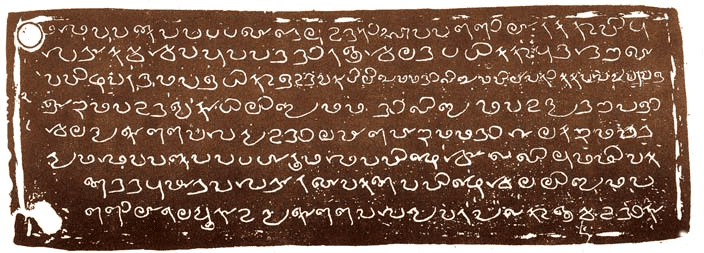

- The rulers introduced the Malayalam language and script in their inscriptions. This development is considered as one of the earliest examples of the use of a regional language in official records in the subcontinent.

- At the same time, the Cheras also drew upon Sanskritic traditions. A 14th-century text, the Lilatilakam, dealing with grammar and poetics, was composed in Manipravalam – literally, “diamonds and corals” referring to the two languages, Sanskrit, and the regional language.

Orissa: The Jagannatha Cult

- In some areas, regional cultures grew around regional traditions eg: Jagannatha cult of Puri (Odisha).

- As the temple gained in importance as a center of pilgrimage, its authority in social and political matters also increased.

- Mughals, Marathas, English East India Company all attempted to gain control over the temple because it could make rule acceptable to local people.

Rajastan: The Rajputs

- The Rajputs are often recognised as contributing to the distinctive culture of Rajasthan.

- Rulers like Prithviraj cherished the ideal of the hero who fought valiantly, often choosing death on the battlefield rather than face defeat.

- Women are also depicted as following their heroic husbands in both life and death – there are stories about the practice of sati.

The Story of Kathak

- Dance form Kathak was originally a caste of storytellers in temples of north India.

- Kathak began evolving into a distinct mode of dance in the 15th and 16th centuries with the spread of the bhakti movement.

- The legends of Radha-Krishna were enacted in folk plays called rasa lila, which combined folk dance with the basic gestures of the kathak story-tellers.

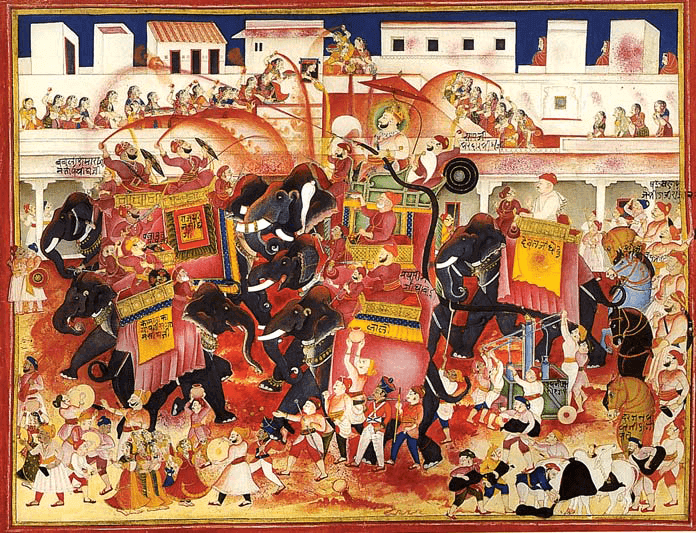

- During Mughal period Kathak acquired a distinctive style which is still followed today.

- Kathak, like several other cultural practices, was viewed with disfavour by most British administrators in the 19th and 20th centuries.

- Recognised as one of “classical” forms of dance in the country after independence.

Miniature Paintings

- As the name suggests, small-sized paintings, generally done in watercolor on cloth or paper.

- Some of these are found in Western India which was used to illustrate Jaina texts.

- With the decline of the Mughal Empire, many painters moved out to the courts of the emerging regional states.

- As a result, Mughal artistic tastes influenced the regional courts of the Deccan and the Rajput courts of Rajasthan.

- Portraits of rulers and court scenes came to be painted, following the Mughal example.

- Himalayan foothills attracted miniature painting which is known as “Basohli”.The most popular text to be painted here was Bhanudatta’s Rasamanjari.

- Kangara school of paintings got inspiration from Vaishnavite traditions. Soft colors including cool blues and greens and a lyrical treatment of themes distinguished Kangra painting.

Bengal: Language and Literature

While Bengali is now recognised as a language derived from Sanskrit, early Sanskrit texts (mid-first millennium BCE) suggest that the people of Bengal did not speak Sanskritic languages. How, then, did the new language emerge?

From the fourth-third centuries BCE, commercial ties began to develop between Bengal and Magadha (south Bihar), which may have led to the growing influence of Sanskrit. During the fourth century the Gupta rulers established political control over north Bengal and began to settle Brahmanas in this area. Thus, the linguistic and cultural influence from the mid-Ganga valley became stronger.

From the eighth century, Bengal became the centre of a regional kingdom under the Palas. Between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries, Bengal was ruled by Sultans who were independent of the rulers in Delhi. In 1586, when Akbar conquered Bengal, it formed the nucleus of the Bengal suba. While Persian was the language of administration, Bengali developed as a regional language.

By the fifteenth century the Bengali group of dialects came to be united by a common literary language based on the spoken language of the western part of the region, now known as West Bengal.Thus, although Bengali is derived from

Thus, although Bengali is derived from Sanskrit, it passed through several stages of

evolution. Also, a wide range of non-Sanskrit words, derived from a variety of sources including tribal languages, Persian, and European languages, have become part of modern Bengali.

Early Bengali literature may be divided into two categories – one indebted to Sanskrit and the other

independent of it.

The first includes translations of the Sanskrit epics, the Mangalakavyas (literally

auspicious poems, dealing with local deities) and bhakti literature such as the biographies of

Chaitanyadeva, the leader of the Vaishnava bhakti movement.

The second includes Nath literature such as the songs of Maynamati and Gopichandra, stories

concerning the worship of Dharma Thakur, and fairy tales, folk tales and ballads. The Naths were ascetics who engaged in a variety of yogic practices.

Pirs and Temples

Pirs were community leaders, who also functioned as teachers and adjudicators and were sometimes ascribed with supernatural powers.

The early settlers in eastern India sought some order and assurance in the unstable conditions of the new settlements. This was provided by Pirs.

The term ‘Pirs’ included saints or Sufis and other religious personalities, daring colonisers and deified soldiers, various Hindu and Buddhist deities and even animistic spirits. The cult of pirs became very popular and their shrines can be found everywhere in Bengal.

Bengal also witnessed a temple-building spree from the late fifteenth century, which culminated in the

nineteenth century. Many of the modest brick and terracotta temples in Bengal were built with the support of several “low” social groups, such as the Kolu (oil pressers) and the Kansari (bell metal workers).

When local deities, once worshipped in thatched huts in villages, gained the recognition of the Brahmanas, their images began to be housed in temples. The temples began to copy the double-roofed (dochala) or four-roofed (chauchala) structure of the thatched huts.

Bengal: Fish as food

Bengal is a riverine plain which produces plenty of rice and fish. Understandably, these two

items figure prominently in the menu of even poor Bengalis.

Brahmanas were not allowed to eat nonvegetarian food, but the popularity of fish in the local diet made the Brahmanical authorities relax this prohibition for the Bengal Brahmanas. The Brihaddharma Purana, a thirteenth-century Sanskrit text from Bengal, permitted the local Brahmanas to eat

certain varieties of fish.

Medieval India: 18th Century Political Formations During the first half of the eighteenth century, the boundaries of the Mughal Empire were

reshaped by the emergence of a number of independent kingdoms. In this post, we will read about the emergence of new political groups in the subcontinent during the first half of the eighteenth century – roughly from 1707, when Aurangzeb died, till the third battle of Panipat in 1761.

The Mughal Crisis

- Emperor Aurangzeb had depleted the military and financial resources of his empire by fighting a long war in the Deccan.

- Nobles who were appointed as governors (subadars) controlled the offices of revenue and military administration (diwani and faujdari) which gave them extraordinary political, economic and military powers over vast regions of the Mughal Empire.

- Peasant and zamindari rebellions in many parts of northern and western India added to these problems.

Emergence of New States

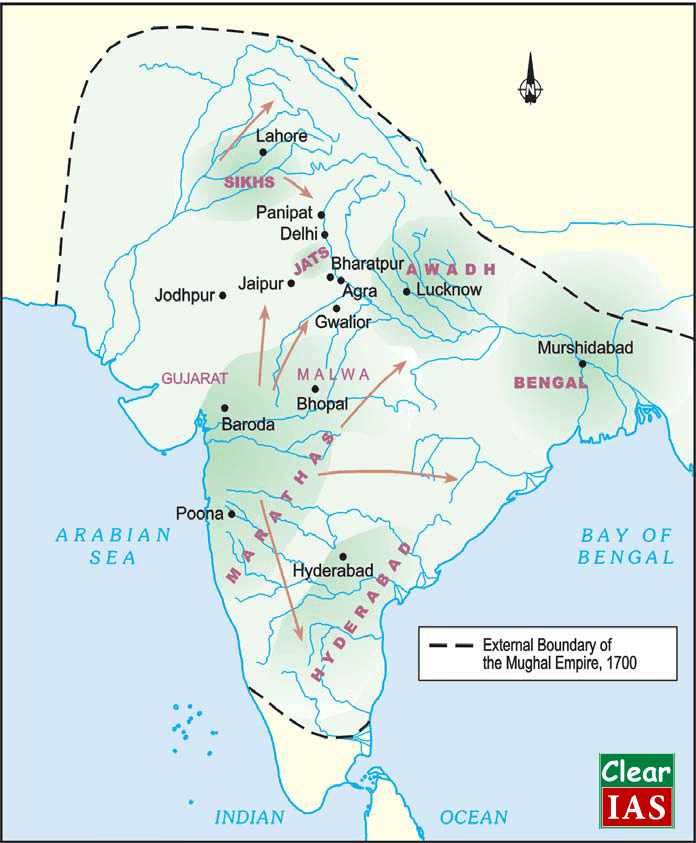

- Through the 18th century, the Mughal Empire gradually fragmented into a number of independent, regional states.

- It can be divided into three overlapping groups:

- States that were old Mughal provinces like Awadh, Bengal, and Hyderabad. Although extremely powerful and quite independent, the rulers of these states did not break their formal ties with the Mughal emperor.

- States that had enjoyed considerable independence under the Mughals as watan jagirs. These included several Rajput principalities.

- States under the control of Marathas, Sikhs and others like the Jats. They all had seized their independence from the Mughals after a long-drawn armed struggle.

Hyderabad

- Nizam-ul-Mulk Asaf Jah, the founder of Hyderabad state, was appointed by Mughal Emperor Farrukh Siyar.

- He was entrusted first with the governorship of Awadh, and later given charge of the Deccan.

- He ruled quite independently without seeking any direction from Delhi or facing any interference.

- The state of Hyderabad was constantly engaged in a struggle against the Marathas to the west and with independent Telugu warrior chiefs (nayakas)

Awadh

- Burhan-ul-Mulk Sa‘adat Khan was appointed subadar of Awadh in 1722.

- Awadh was a prosperous region, controlling the rich alluvial Ganga plain and the main trade route between north India and Bengal.

- Burhan-ul-Mulk held the combined offices of subadari, diwani and faujdari.

- Burhan-ul-Mulk tried to decrease Mughal influence in the Awadh region by reducing the number of office holders (jagirdars) appointed by the Mughals.

- The state depended on local bankers and mahajans for loans.

- It sold the right to collect the tax to the highest bidders. These “revenue farmers” (ijaradars) agreed to pay the state a fixed sum of money. So they were also given considerable freedom in the assessment and collection of taxes.

- These developments allowed new social groups, like moneylenders and bankers, to influence the management of the state’s revenue system, something which had not occurred in the past.

Bengal

- Bengal gradually broke away from Mughal control under Murshid Quli Khan who was appointed as the naib, deputy to the governor of the province and he was neither a formal subadar .

- Like the rulers of Hyderabad and Awadh, he also commanded the revenue administration of the state.

- In an effort to reduce Mughal influence in Bengal he transferred all Mughal jagirdars to Orissa and ordered a major reassessment of the revenues of Bengal.

- Revenue was collected in cash with great strictness from all zamindars.

- This shows that all 3 States Hyderabad, Awadh, Bengal richest merchants, and bankers were gaining a stake in the new political order.

The Watan Jagirs of the Rajputs

- Many Rajput kings, particularly those belonging to Amber and Jodhpur, were permitted to enjoy considerable autonomy in their watan jagirs.

- In the 18th century, these rulers now attempted to extend their control over adjacent regions.

- So Raja Ajit Singh of Jodhpur held the governorship of Gujarat and Sawai Raja Jai Singh of Amber was governor of Malwa.

- They also tried to extend their territories by seizing portions of imperial territories neighbouring their watans.

Seizing Independence

The Sikhs

- The organisation of the Sikhs into a political community during the seventeenth century helped in regional state-building in the Punjab.

- Guru Gobind Singh fought against the Rajaput and Mughal rulers, after this death, it was under Banda Bahadur’s the fight continued.

- The entire body used to meet at Amritsar at the time of Baisakhi and Diwali to take collective decisions known as “resolutions of the Guru (gurmatas)”.

- A system called rakhi was introduced, offering protection to cultivators on the payment of a tax of 20 per cent of the produce.

- Their well-knit organization enabled them to put up a successful resistance to the Mughal governors first and then to Ahmad Shah Abdali who had seized the rich province of the Punjab and the Sarkar of Sirhind from the Mughals.

- The Khalsa declared their sovereign rule by striking their own coin in 1765. The coin was same as that of Band Bahadur’s time.

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh reunited the groups and established his capital at Lahore in 1799.

The Marathas

- Another powerful regional kingdom to arise out of a sustained opposition to the Mughal rule.

- Shivaji (1627-1680) carved out a stable kingdom with the support of powerful warrior families (deshmukhs). Groups of highly mobile, peasant- pastoralists (kunbis) provided the backbone of the Maratha army.

- Poona became the capital of the Maratha kingdom.

- After Shivaji, Peshwas[principal minister s] developed a very successful military organisation by raiding cities and by engaging Mughal armies in areas where their supply lines and reinforcements could be easily disturbed.

- By the 1730s, the Maratha king was recognised as the overlord of the entire Deccan peninsula. He possessed the right to levy chauth[25 per cent of the land revenue claimed by zamindars]. and sardeshmukhi[9-10 per cent of the land revenue paid to the head revenue collector in the Deccan] in the entire region.

- The frontiers of Maratha domination expanded, after raiding Delhi in 1737, but these areas were not formally included in the Maratha empire but were made to pay tribute as a way of accepting Maratha sovereignty.

- These military campaigns made other rulers hostile towards the Marathas. As a result, they were not inclined to support the Marathas during the third battle of Panipat in 1761.

- By all accounts cities[Malwa, Ujjain etc] were large and prosperous and functioned as important ant commercial and cultural centers show the effective administration capacities of Marathas.

The Jats

- Jats too consolidated their power during the late 17th and 18th-centuries.

- Under their leader, Churaman, they acquired control over territories situated to the west of the city of Delhi, and by the 1680s they had begun dominating the region between the two imperial cities of Delhi and Agra.

- The Jats were prosperous agriculturists, and towns like Panipat and Ballabhgarh became important trading centers in the areas dominated by them.

- When Nadir Shah (Shah of Iran) sacked Delhi in 1739, many of the city’s notables took refuge there.

- His son Jawahir Shah had troops and assembled some another from Maratha and Sikh to fight Mughal.

Emergence of British as a Supreme Power

No comments:

Post a Comment